The magisterial book, Modern Political Economics (MPE), by Yanis Varoufakis, Joseph Halevy, and Nicholas Theocarakis is a tour de force. The subtitle of the book expresses its major theme: Making sense of the post-2008 world. But this is not another book about corruption on Wall Street. Or rather, it is, but it is more importantly a book that reveals how far the practice of economics has systematically strayed from the real world and how far the real world has strayed from a rational order.

The book has two parts: first, a major review and critique of the enterprise of political economic theory and second, an historical survey of the post-WWII world leading up to the crash of 2008. The economic theorists critiqued in Book I include Aristotle; the physiocrats; Adam Smith; David Ricardo; Karl Marx; the early marginalists, William Stanley Jevons and Alfred Marshall in England and Carl Menger, Eugene von Böhm Bawerk, and Friedrich von Weiser in Austria; the equilibrium theorists including the Frenchman Leon Walras; the dissenting marginalist John Maynard Keynes; and finally, the founders of neo-classical economics: John Nash, Gerard Debreu, and Kenneth Arrow. Along the way contributions of major figures like J. B. Say, John von Neumann, Joseph Schumpeter, Paul Sweezy, Friedrich Hayek, and Paul Samuelson are reviewed and critiqued. Book II presents their novel story of the Global Plan and the Global Minotaur.

Unlike most treatments of economics, however, this book is dominated by a pervasive scepticism of the very idea of successfully formulating a closed system of equations which can in any way be said to represent real economies. They show a deep appreciation for the sceptical tradition. Two out of the three authors are Greeks, of course. And while the names of Sextus Empiricus and Pyrrho are nowhere mentioned in the book, the classical Sceptic’s legacy of rational critique of dogmatism pervades this book.

Key original concepts of the book include:

- Inherent error and lost truth

- Condorcet’s secret

- Radical indeterminacy

- The fundamental theorem of Marxism and the mechanization of the economy

- The Meta Axioms

- The Global Plan and the Global Minotaur

- The rise of private money

Each one of these concepts is worth talking about.

Inherent Error and Lost Truth

The great difference between natural science and any study of the human world is that (until the arrival of quantum mechanics) humans can (could) study the natural world from a perspective of distance that would allow them to consider themselves abstracted from that world. This, of course, is not possible with study of the human world. In spite of this, humans have persistently tried to apply the success that had been achieved in natural science to the understanding of human affairs. The inherent error in this as it applies to political economy shows up when (typically) attempts are made to close systems of mathematical equations purporting to represent a system which is affected by the equation system itself. Inevitably these attempts founder on the rocks of self-contradiction. A key inherent error of economic theories is “an error caused by a definite feature of human, market societies: value can never be independent of the distribution of social power over the surplus produced by human labour and ingenuity. Social power is determined by our valuation of things, of people and of their ideas and, at once determines these values. This infinite feedback between value and power lies at the heart of economics’ Inherent Error, ensuring that all economics that overlooks it, or tries to ‘solve’ it by technical means, is bound to produce a profoundly misleading theory of society.”

An illustration of this tendency towards inherent error in economic theory occurs in theories of growth and value. Varoufakis et al. argue that “overcoming economics’ Inherent Error and procuring a logically consistent theory of value within a useful theory of growth is more than just difficult. It is impossible!” This inherent error shows up over and over again in their history of economic theory:

“Ricardo’s insistence of squaring his value theory with a theory of growth led to Malthus’ devastating critique; Marx’s desperate attempt to close his model led to the transformation problem and the contorted logic required for its resolution; the marginalists’ insistence of explaining all prices and quantities by means of the equi-marginal principle forced them, eventually, to stick to Robinson Crusoe-like economies, etc.”

I will look in more detail at their analysis of Karl Marx’s wrestling with this problem of inherent error in a subsequent paragraph.

The typical development in the history of economic theory when these difficulties are exposed is to replace the failed theory with another, which eventually leads to the same fate. But, meanwhile, important truths uncovered by the previous theory are forgotten. This presents the correlative problem of lost truths:

“The trouble with these failures was that, once their logical incoherence became apparent, and the political order no longer had uses for them, they led the following generations of economists to drop them wholesale, together with the important insights contained within. And if this has not happened just yet with neoclassicism, because of its continuing political utility, eventually it will.”

Condorcet’s Secret

Economics, whether it admits it or not, is about managing surplus. From the reign of the Pharaohs to the rise of Wall Street a key task of political economics has been to explain and either justify or declaim the command exercised by the ruling elite over the surplus of value created by collective labor. Because this surplus comes from the work of the majority, yet is enjoyed for the most part by the ruling elite, a ruse must be played on the majority. But the raw power of the majority is always greater than that of the few in ruling elites. This reality was captured by the French thinker Condorcet when he wrote in 1794 “force cannot, like opinion, endure for long unless the tyrant extends his empire far enough afield to hide from the people, whom he divides and rules, the secret that real power lies not with the oppressors but with the oppressed.” These are the “mind forg’d manacles” of Blake; the consent of the many to the exercise of power by ruling elites.

Radical Indeterminacy

A parallel fact about economic theory to its tendency to inherent error is what the authors call its “radical indeterminacy.” In a chapter titled “The Trouble with Humans” they explore the reasons why an economy composed of humans resists quantification in a way an economy composed solely of machines would not. In this chapter they make much of the story told in the commercial movie “The Matrix” in which a future economy of automatons on planet Earth has no need for humans except as a source of energy. Human heat is harnessed and captured to use as batteries to power the Matrix Economy.

They credit Karl Marx with being the first to discover a crucial fact about labor, that of its “ontological indeterminacy”. This chapter argues that “without the indeterminacy of labour inputs no economy is capable of producing value. In short, our economic models can only complete their narrative if they assume away the inherent indeterminacy that is responsible for the value of things we produce and consume.”

Radical indeterminacy was also appreciated by John Maynard Keynes. At several points in the book the authors stop to recognize Keynes’ answer to the question why capitalists invest: “We are damned if we know!” Keynes use of the term “animal spirits” for why capitalists act in the world the authors consider “a major own goal” because it led to criticism of Keynes for attributing irrationality to the capitalist system when what he really had discovered was its radical indeterminacy.

The Fundamental Theorem of Marxism and Mechanization of the Economy

Varoufakis et al. are, in general, sympathetic to the critique of political economy provided by the towering figure of Karl Marx. Their approach to economics in the face radical indeterminacy is to turn to history. This approach is certainly influenced by Marxian analysis. Marx’s analysis of the crises of capitalism is also highly compatible with their own.

But before they travel away from closed theory to historical analysis, they discuss the attempts by Marx to capture a theory of capitalism. Following Michio Morishima, they call the following equation the “Fundamental Marxian Theorem”:

π = e / (1 + k)

Where,

π = Rate of profit

e = Rate of exploitation (or extraction) = s / v

s = Surplus value = λ – c – v

λ = Total value of product

c = Constant capital = raw materials + auxiliary materials + machinery depreciation

v = Variable capital (labor)

k = Organic composition of capital or the rate of mechanization

= (c/v)

The surplus, s, derives from value produced by the laborer during the working day (Chapter 10 of Capital, Volume I) in excess of the value of his means of subsistence. The surplus, s, is at least partly due to the cooperation which takes place among humans working together. Since the capitalist negotiates his labor contract with each laborer independently, the surplus goes wholly over to the capitalist. Marx outlines this process in Chapter 13 of Volume I of Capital.

The degree of exploitation, e, is developed in Capital, Chapter 9. This represents the ratio of surplus to the total labor value. It is the measure of surplus relative to the amount of labor applied to a productive process. Varoufakis et al. term this, rather than the rate of exploitation, the rate of extraction; because this has less of a pejorative connotation, but also because this parallels the extraction of value from humans in the Matrix Economy.

The factor, k, in the fundamental theorem Marx calls the “organic composition of capital.” But Varoufakis et al. emphasize that this factor represents the degree of mechanization in the productive process. Because this tends to increase as capitalism develops in time and because there must be some limit to the amount of surplus value that can be extracted from workers, this equation provides a mathematical formulation of Marx’s long-term prediction of a falling rate of profit in capitalist societies, an end which Marx saw as inevitably apocalyptic for the capitalist system.

In the shorter term, however, this equation provides a way to follow cyclical crises of capitalism. In an upswing k rises and although production increases, profit rates fall. Capitalists eventually stop investing and reduce production or go bankrupt. This produces unemployment which produces a reduction in demand. With fewer firms as many go bankrupt, the prices of labor power and materials drops. This produces a stimulation of rates of profit which drags the economy out of the mire.

So with one simple equation, Marx had found a basis for cyclical crisis in capitalist economy and a justification to believe that in the long term, the dynamic of capitalism would cause it to run down. The problem came when Marx tried to apply this model, in Volume II of Capital, to a multi-sector economy. In the simplest version of such an economy, an economy with two sectors:

π1 = e1 / (1 + k1) = π2 = e2 / (1 + k2)

The problem here is that capital and labor will migrate between sectors such that the rates of profit in the different sector will tend to equalize. But the only way that the profit rates in different sectors can be the same, unless the organic composition of capital in the two sectors, k1 and k2, is the same, is if the rates of exploitation, e1 and e2, diverge. But migration of labor between the sectors would cause profit rates to diverge, causing capital to migrate to the more profitable sector. So instead of discovering the key to the long-run demise of capitalism, Marx had instead discovered a deep tendency to flux. What was equally concerning was that here he had discovered another factor affecting the rate of profit, besides of the surplus value extracted from labor power.

The Transformation Problem

The “transformation problem” is the difficulty with which classical economists, Smith and Ricardo, tried to explain how underlying values are transformed into prices. Their answer to this question was that “equalization of profit rates will bring about prices at which each commodity exchanges with others at a rate (or relative price) reflecting the relative labor inputs necessary during their production.” The “serious” problem that the authors see with this solution is that “when machines assist human labour in the production process, an increase in labour costs (relative to the cost of the machines) changes the value of all commodities.” Adam Smith assumed that “the wage share of the surplus (and thus the price of labour relative to machines) remains constant.” Ricardo, who did not want to make this assumption, left himself open to the critique of Thomas Malthus that “for Ricardo’s labour theory of value to hold water, each commodity had to be produced by the same technique of production involving the same proportions in the use of the various inputs. Ricardo meekly replied that his theory could be seen as an approximation.”

Marx was also faced with the Transformation Problem. The “only way of maintaining his own theory of value and keep alive the idea of a uniform rate of profit when capital utilization differs across sectors was to accept that the rate of labour input extraction is not the same across sectors. But then he had to explain why those rates differed.” The problem with this conundrum was that Marx was unsuccessful (in the author’s opinion) in coming up with a theory that solved the transformation problem (like accepting the empirical fact of differing extractive power of some employers over others) that did not threaten his major thesis that surplus value was the exclusive source of profits. The limit to this acceptance would be to have to acknowledge that “an increase in the economy-wide wage rate may indeed lead to an increase in economy wide prices (i.e. inflation)” an admission that would contradict his speech “lambasting” Citizen Weston at the First International Working Men’s Association meeting in June 1865.

The Meta-axioms

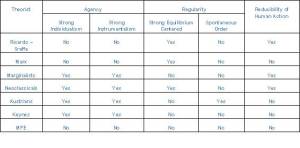

As a summary of Book 1, the authors present a matrix of characteristics of the historical schools of economic analysis included in their survey. The economic analysis schools and their “meta-axioms” are summarized in the table below. These meta-axioms are higher order axioms which underpin all of the theory. The first three meta-axioms underlie all of neoclassical economics, the development of marginal theory into equilibrium models conceived originally by Leon Walras and developed by the dominant stream of the American economics profession. The fourth meta-axiom evolved and was followed only by the Austrian school. The fifth meta-axiom, reducibility of human action, is the idea that human beings can be thought of as reducible to machines.

1st Meta-axiom –Methodological Individualism

The first meta-axiom is embraced by the marginalists, including the neoclassicals and the Austrians. The authors also give Keynes a tick mark in this column. This is the premise that “all explanations are to be sought at the level of the individual agent.” This is the world of Robinson Crusoe dominated by preferences that can be considered prior to the system that seeks to explain his action. The authors consider stronger and weaker versions of this underlying axiom. The weaker versions leave room for consideration of how the individual could evolve and develop a “mutually influential relation within the social structure within which she acts.” The strong version is of lone Crusoe making decisions in isolation from the rest of the world. This meta-axiom is a characteristic break from the classical economists Smith, Ricardo, and Marx who all focus on the economic system as a whole. The strong version is a rejection of the concept of dialectic; for Marx the individual cannot be conceived in abstraction from the society that produced him. The neoclassical break from this is the beginning of a flight from the real world.

2nd Meta-axiom – Methodological Instrumentalism

The second meta-axiom insists that while individual agents must have reasons for their actions, these reasons must be exclusively instrumental; they must serve “specified ends which are definable in terms of some mathematical function of ‘success’”. People are motivated by preferences to which they are fully committed and which fully explain their behavior. Lack of understanding, luck, and misadventure are ruled out by definition. Since the classical economists were not committed to the first meta-axiom, they are not committed to the second.

3rd Meta-axiom – Methodologically Imposed Equilibrium

The authors call this “the linchpin of the neoclassical method.” A primary thesis of the entire book is that that economic theories (because of inherent error) can not accommodate both time and complexity in the same model. This assumptions of neoclassical economics do away with time. The classical economists, including Marx, assumed that economies tend toward equilibrium. The neoclassical economists made the strong version of this fundamental axiom central to their (vain) attempt to close their systems; only behavior consistent with the model’s assumption of equilibrium is admitted.

4th Meta-axiom – Spontaneous Order

This meta-axiom is unique to the Austrian school. While the Austrians, like Keynes, denied the strong version of the equilibrium assumption, and had full appreciation, like Keynes and Marx, for the indeterminacy of the human element in economies. But the Austrians were deeply committed anti-socialists and at all costs sought a substitute for any equilibrium that might turn out to be socialism. So they proposed that “due to the irreducibility of human knowledge to some well-defined mathematical function, no central plan and no collective agency (i.e. a state, a municipality, a club) can generate social outcomes. Thus the Austrians sought regularity in the spontaneous order resulting from free intercourse . . . between persons.” That preexisting power relationships prevent such free intercourse was conveniently ignored.

5th Meta-axiom – Human Reductionism

The last of the meta-axioms, which Varoufakis et al. treat only briefly, is “whether the mind-frame of the thinkers in each different row is predicated upon human reductionism, upon, that is, a readiness to think of men and women, indeed of children too, as analytically equivalent to machines, to a mathematical mapping of outcomes to some index of preference satisfaction, or at best, to the algorithms running our magnificent computers.” They condemn the classical economists, Smith and Ricardo, the marginalists, and the neoclassical economists of this perversion. They credit Marx as the “. . . first political economist to have based an important economic insight on the irreducibility of the human person to a quantifiable, machine-like entity . . .” They also find Keynes and the Austrians innocent of this demeaning meta-axiom.

The bottom line of the table indicates the position of the authors on these five meta-axioms: they deny assuming that any of them are true. For this suspension of judgment I award them the title “Sceptic”. But if economic systems are radically indeterminate, what to do, how to understand them? If you deny all of the meta-axioms, how to make sense of the world that surely exists?

Keynes recognized indeterminacy in the decision to save or to invest. But it was Marx who recognized the indeterminacy that resides in the “life-giving force that runs through capitalism bestowing value and even life upon mere ‘things’, albeit only as long as it remains indeterminate; irreducible, that is to an electricity-like force. It is this vivifying, indeterminate energy that creates capital out of mere machines, a relatively newfangled force with the astonishing capacity to both liberate and to enslave the humans that work it and, with equal force the humans that own it”. That indeterminate force is human labor.

They therefore praise the understanding that shows the dialectical nature of both labor and capital. “Our hypothesis is that to make sense of capitalism we need to capture both (the dynamics of the capitalist system) and (the ways in which irrepressibly free humans become increasingly enslaved by their artifacts) and to combine them with Keynes’ successful escape from the Inherent Error.”

They seek to introduce as data the sources of indeterminacy: 1) “the irreducibility of human input” and 2) “the irreducibility of human forecasts to a well-defined mathematical expectation function” without resorting to the assumption of either equilibrium (which they consider to be Marx’s mistake) or spontaneous order (“as is the Austrian’s religious wont”.)

But how to make sense of this indeterminacy? The authors disavow both relativism and determinism. They hope to maintain a “pluralist disposition” equipped with an understanding of “the necessary, but erroneous, viewpoints provided by the different shades of political economics in the preceding pages” to attempt an explanation similar to the physicists explanation of why the stick half-immersed in water and appearing bent, is really straight. Their answer is given in the second part of their book: by historical analysis.

The Global Plan and the Global Minotaur

The second part of the book includes this historical analysis of the post-World War II world. They divide this time frame into two periods: 1) The Global Plan: the period following the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 which set up the gold-backed dollar as the world’s dominant currency and 2) The Global Minotaur: the period after the breakup of the Bretton Woods system leading to the financial crash of 2008. This is the story of a march to devastating collapse. The third period would be our current time, the period of aporia following 2008. This story is also retold in a solo 2011 book by Varoufakis, The Global Minotaur (TGM).

The Global Plan

The Global Plan begins during the waning of WWII at the international conference convened by Franklin Roosevelt at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in July 1944. The conference provided a face-off between the two primary partners in the Allied war effort: The United States, represented by Harry Dexter White, and the United Kingdom, represented by none other than John Maynard Keynes. The conference was focused on two ostensible goals: 1) design of a post-war monetary system and 2) reconstruction of Europe and Japan. Underlying issues, however, were how to prevent future lapses into Great Depression and who would be in control of what was recognized needed to be an international approach to managing the world economy.

At this conference Keynes made one of the most striking proposals to ever reach the bargaining table of an international conference: an International Currency Union (ICU) that would provide a single currency (which Keynes christened the “bancor”) for the whole capitalist world. This would replace the Gold Standard that had been killed off by the Great Depression. The ICU would provide the stability provided by gold without the severe restriction that killed the Gold Standard: “the fact that by restricting the quantity of money in each country to a pre-specified level linked to gold deposits, it prevented governments from dealing with catastrophic declines in effective demand (e.g. the Crash of 1929) by means of increased public expenditures.” Keynes thought that this mechanism would provide a means to deal with two devastating problems: catastrophic crashes and systematic trade imbalances. The ICU would guard against trade imbalances by allowing member countries to borrow at zero interest up to a deficit of 50% of the country’s average trade volume. Beyond that there would be s fixed interest rate. This would give an incentive to minimize excessive debt. For countries exceeding a certain percentage of their trade volume interest would also be charged and its currency would therefore have to appreciate and in the process transfer that surplus to deficit countries.

Keynes’ brilliant idea was an idea before its time. The United States, as the emerging victor in the world war, was in no mood to give up its hegemonic position. White vetoed Keynes’ plan and in its place proposed the system that was adopted: a system of fixed exchange rates with the dollar as its base, albeit tied to gold. To address the problem that there was no mechanism here to deal with depression or fiscal default, the adopted plan established the International Stabilization Fund which became the International Monetary Fund (IMF). White was to go on to the job of executive director of the IMF before being forced out under a cloud of Cold War mania. The problem of trade imbalance went unaddressed. It took another 30 years before the United States itself would find itself as the world’s largest deficit economy and come up with the system which made a virtue out of apparent economic failure (deficit).

The Global Plan was administered by New Dealers who had been trained following the insights of Keynes from the General Theory but who, as representatives of the world hegemon, needed to turn their attention to maintaining that hegemonic power. During the years following WW II the United States was a surplus economy and it recycled its surplus by supporting reconstruction in Europe and Japan. The German Deutschmark and the Japanese Yen became supporting currencies to the dominance of the US dollar. But the Global Plan came to an end with the end of the 1960s when the Vietnam War and the Great Society turned the United States from a surplus to a deficit economy.

An interesting side-story in MPE is the story that it tells about encouragement of the Middle Eastern oil price rise by Secretary of State Kissinger with the thought that while the United States would be harmed by oil price inflation, Germany and Japan would be harmed more. The inflation that followed in the seventies doomed the Global Plan. When the French sent a warship to the United States to redeem their dollars for gold, Nixon unhooked the United States from gold convertibility and imposed wage and price controls. The Global Plan was dead. But what was to follow? What was to follow was an ingenious scheme for the United States to maintain its hegemony even as a deficit economy: The Global Minotaur.

The Global Minotaur

The Minotaur, of course, was the monstrous result of the coupling of the wife of King Minos of Crete with the beautiful white bull given to King Minos by Poseidon. Aphrodite had driven the wife mad with love for the bull, which Minos had kept in his household, instead of sacrificing it, as Poseidon had intended. This offspring, being an unnatural result, had no sense of proper nourishment and desired human flesh as food. Minos hired Daedalus to design him a Labyrinth in which to house the beast and required the Athenians, who were under his power as a result of a successful military campaign, to send young men and women to Crete for sacrifice.

For Varoufakis the myth of the Minotaur provides a fitting image of the power of the United States to maintain its hegemony over the world economy even as it became a deficit economy. The system, as described in MPE and TGM, is one in which the United States had accumulated massive fiscal and trade deficits in the Post-Reagan years. The trade deficit reached nearly $800 billion dollars per year by 2007. The current post-2008 fiscal deficit is over one trillion dollars per year.

The Matrix Economy makes a showing here as a steadily rising productivity accompanied by stagnation in real wages. Where did the increased productivity go? It went into average real profits, of course, which, by the time of the 2008 crash had reached 7 times the amounts at the beginning of the Global Minotaur era in the 1970s.

But how does this work? How is it possible that a country massively consuming less than it produces and accumulating debt can keep afloat? Well, the long-term answer is that it can’t; for this has led to the crash of 2008 and to our current crisis. But how is it that it lasted so long? The answer that Varoufakis gives is “financialisation”. The surpluses accumulating in the Central Banks of China and Germany during the last 20 years have been recycled by purchase of United States Treasury Bonds and other securities with the money passing through the financial centers of London and New York. With the United States maintaining a reasonable control of internal inflation, US investments became not only less expensive, but more secure.

Loans were made by US-based banks during the sixties and seventies to developing countries in Latin America and several former members of the Eastern Bloc at low interest rates. As interest rates rose in the mid-1970s, these developing countries were caught in a debt repayment squeeze. Forced to go to the IMF for help, these countries were forced to dismantle their public sectors and to sell off valuable public assets, like water and telecommunications utilities, which were scooped up by Western companies at bargain basement prices.

“To recap, the nexus between geopolitical power and the centrality of the dollar’s role in maintaining the Global Minotaur grew stronger and stronger. A brief perusal of the Fed’s research papers during the 1990s confirms that US authorities saw the greenback as a strategic asset. The drive to use political influence in order to dollarise whole foreign economies, especially in Latin America in the 1990s, is to be understood as part of the same mindset. Dollarisation meant that the dollar became the country’s de-facto local currency. . . . . As dollars were increasingly demanded by foreigners also for their own domestic purposes, the United States’ balance of payments played a decreasing role in shaping the dollar’s value in the international money markets . . . . The deep, and deeply wounding (for local societies), crises that dollarisation led to in the later 1990s were, in this sense, mere collateral losses during the process of maintaining the Minotaur.”

The Rise of Private Money

By 2003 the United States was devouring over 70 per cent of global capital outflows. “Mountains of cash flowed to Wall Street and from there to US corporations in the form of equity and loans.” This caused an enormous increase in the profitability of US corporations. This flow of cash was magnified by the creation of what amounts to private money, the new forms of derivative investments known as “collateralized debt obligations” or CDOs and their evil twins, credit default swaps, or CDSs. “The CDOs were options or contracts. In reality, and since no one knew (or really cared to know) what they contained, they acted as a form of private money that financial institutions and corporations used both as a medium of exchange and a store of value.”

Friedrich Hayek had actually proposed with favor a system of private money in an astounding 30-page paper from 1976, Denationalisation of Money. Hayek blamed the Federal Reserve for the Great Depression. He thought that they had printed too much money in the 1920s. The moral that he drew from this story was that government could not be trusted to print money and that private banks should have the right to issue their own money. It seems to the authors that this is exactly what happened in the run-up to the 2008 crash; A fitting testament to a truly strange Nobel Prize winner in the strange “science” of economics.

The authors end their story of the Global Minotaur with the following summary: “Keynes believed that he had a simple solution to capitalism’s tendency to stumble, fall and refuse to pick itself up without a helping hand from the state . . . . judicious fiscal and monetary adjustments . . . He was wrong. Capitalism cannot be civilized, stabilized or rationalized. Why? Because Marx was right. Increasing state power and benevolent interference will not do away with crises. . . . Marx too thought he had a simple answer for capitalism’s troubles. Convinced that its own contradictions would, effectively, force it to commit suicide; he believed that a new rational order . . . was inevitable. He too was wrong. Why? Because it has Keynes (or someone with similar ideas) on its side. . . . Regulation and state intervention do save capitalism from itself, in the limited sense of preserving property rights and buying time for capital to overcome the authorities’ renewed ambition to reign it in. . . . . The hegemon minding the shop decided to help itself to the till. . . . . Then the bubble broke, the private money burnt out . . . . and a ping-pong game began with private losses turning into public debt. . . . The problem with this type of cycle is its irregularity. Like an out of control pendulum, it threatens to exhaust the state’s capacity to bounce back because of a collapse of the state’s financial position.”

The Post-2008 World

The Crash of 2008 has deeply wounded or perhaps killed the Global Minotaur. But what will replace it as the Global Surplus Recycling Mechanism (GSRM)? In TGM Varoufakis proposes two possibilities. The first is a “grand coalition of emerging countries, which would forge a de facto GSRM on the basis of planned investment and trade transfers between them. . . . . Such agreements between Brazil, China, Argentina, India, Turkey, and selected African countries could act as a GSRM that would promote stable growth. The fact that it would leave our Western bankruptocracies out on a limb would be icing on the cake.” The second takes off from Keynes’ proposal for an ICU at the Bretton Woods conference. He quotes the now disgraced Dominque Strauss-Kahn (DSK) in favor of this possibility. Given the enormous military might of the United States, the prospects look pretty grim to this reviewer. But why not end on an upbeat note: “Perhaps centuries later, our own Minotaur’s death will inspire the poets and the myth makers to mark its demise as the beginning of a new, authentic humanism” (the concluding lines of TGM.)

For another review of this book see: http://monthlyreview.org/2011/06/01/the-emperor-has-no-clothes%E2%80%94but-still-he-rules.

I hope our discussion can consider in order the validity of TGP, then TGM, and then how realistic or plausible are the possibilities of a viable GSRM..

This masterful summary is entrancing because it gives me the confidence (no doubr misplaced, but so what?) that I can understand what is being explicated…

Side topic, for which there won’t be time: it would be tempting for me to consider what a late colleague, sociologist Richard Brown, called “the aesthetics of theory” — I think he meant how the elegance or originality of the form or shape of concepts may enhance or detract from their acceptance of or prominence in intellectual history.

Charlton,

I look forward to critical conversation on this very compelling attempt at a “story behind the story” of the build-up to 2008. Martin Wolf had been writing in the Financial Times for several years before the 2008 crash about the unbalance in the world trading system. He was one of the few in the world press who did. But he never came to a clear statement that the emperor was unclothed. This story is also beyond the one told by Robert Reich and Paul Krugman of an economy that could be fixed by better tax policy and a bigger fiscal stimulus. It gets behind the scenes in the daily press to look at the long-term narrative.

As for Richard Brown; never heard of him, but look forward to hearing more. The attractions of elegant models that close only by departing from the planet inhabited by us humans is very much a common theme in Part I of MPE. This part of MPE seems as much as anything a show of the authors’ frustration at having to spend so much time studying the various neoclassical fantasies in order to get through graduate school.

Ciao,

Randal